By Julianna Dotten

I know. It’s a big step. The days of elementary school stories and paragraph-writing are over. Your student is ready to take the leap into the world of theses, propositions, and MLA. Where do you begin? Let me share the tips that have fed my passion for the essay.

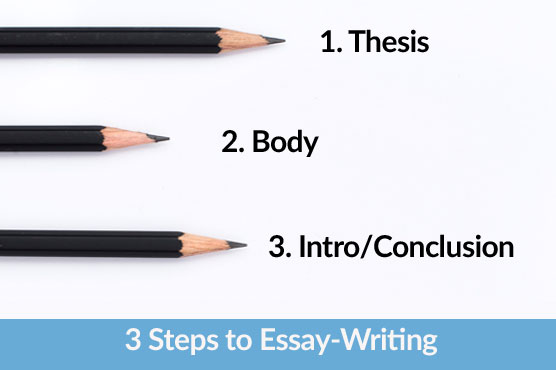

1. Write to a thesis.

I was writing essays and even inserting thesis statements for years before I really grasped the foundation of persuasive writing. In my first college class, my professor handed us an overview of a thesis and said, “In this college, you’re expected to write to a thesis.” Suddenly, it all clicked. This is what my writing teacher (my mother) had been trying to tell me all along.

So what is a thesis?

Writers – like all good communicators – don’t just spit facts back out. They demonstrate an argument, a thesis. They maintain a point of view, and their goal is to convince you of their position. That’s the basis of persuasive writing.

It’s also the basis of the persuasive essay. You take an argument (which you sum up in the sentence in your introduction called the thesis statement) and logically argue why your argument is correct. It requires a level of thought not necessary in a simple repetition of facts.

It’s not difficult to get a book from the library and then spit out facts about a character or an event onto the page. But to analyze and argue for or against an idea improves the thinking capacity by leaps and bounds. After all, isn’t that the whole goal of education: to develop the fine art of thinking?

Here’s an example. Writing about George Washington’s Life requires a mere repetition of facts. You could write a paragraph about his birth and childhood years, another one about his involvement in the French and Indian War, and another on his role as commander-in-chief and president of the United States. Although the topic might be interesting, the lack of argument will leave the essay dull and empty.

On the other hand, an essay with a thesis statement such as this would argue a distinct point: George Washington laid the foundation of the strong moral character for a century of American presidents by his communication skills, his firm faith in God, and his perseverance through difficulty. This sentence outlines outlines both an argument (a thesis) and strong reasons why that argument is true.

2. Write your body.

Once you’ve written your thesis statement (which should include your points, or reasons for your argument), it’s simply a matter of explaining each point and using stories, statistics, or facts to support it. This is where your research comes in. Can you find an interesting story or fact that illustrates your point? If not, you should reconsider your argument.

Most basic essays include three points, with at least one paragraph for each point. It’s a balanced number for rounding out an argument. As you get more familiar with the essay, you can branch out to more or less points or even detailed outlines with subpoints and complex arguments. But if you can think of three, you’re doing great.

3. Write your introduction and conclusion.

This is the fun part! Introductions are a classic bait and switch. Find something that pulls the reader into your topic so he just can’t put your essay down! This could be a story or anecdote, a quote, a profound or shocking statement, or a question — all leading up to your thesis statement. This is where you can leave the strict logic of the rest of the essay and get your creative juices flowing!

In the conclusion, you’ll want to summarize where your argument has gone. The conclusion is not the place to add new information. Instead, find a way to circle back to your introduction and/or title. Restate your thesis statement, but try to find a different way to say it. Then, find an inspiring way to end the essay.

Perhaps you can branch out and talk about the impact of your topic at large. Or, if your argument is a call-to-action, use the end to inspire your readers to want to get up and go make a difference. One of my favorite methods is to use three simple sentences that stand out to the reader. Keep on. Don’t give up. Your reward will come.

At the beginning, you’ll want to encourage your student to start with a familiar topic. If you’ve been studying a topic in history or reading a biography, brainstorming an argument will be much easier. Even more, try to find a topic he’s passionate about. My brother (not the writing type) suddenly gets energized when he’s asked to write about politics, economics, or hunting.

You can tell when you’ve hit a person’s hot button in a conversation. Ask questions until your student just can’t stop talking about a subject, and you’ll know you’ve found his passion.

Those are just a few basics that have helped me time and again. More importantly than getting all the details down, just encourage your children to love writing, and they’ll figure out the rest in time. And even if they’re not the writing type, they’ll have the experience and basics to survive through high school and college classes.

Very helpful article! You brought this daunting task back to basics with such easy-to-understand tips. Thank you for taking the time to share it!

Excellent tips I can put to good use right away! Thanks!